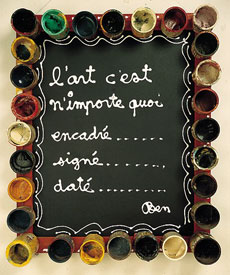

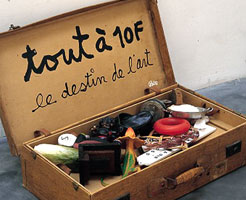

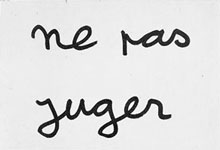

Any Thing (N'Importe Quoi)

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Composition 1960

# 3 Announce to the audience when

the piece will begin and end if there is a limit on duration.

It may be of any duration. 5 - 14 - 60 |

Announce to the audience that

the lights will be turned off for the duration of the composition

(it may be any length) and tell them

when the composition will begin and end. 6 - 3 - 60 |

Composition 1960 # 13

November 9, 1960. |

Surprise Box The surprise box has a top with a hole in it large enough to put your hand through it. One person puts something into the box, anything. A second person comes when the box has been left alone, and reaches into the box to find what has ben left inside. He may feel around fast or slow, depending on how much suspense he wants to feel. Pretty soon he will find what's in the box. He can then do whatever he likes with what he found. He then can put something else in the box for the next person to find. |

|

This is the piece that is any piece. Tony Conrad, Summer 1961 |

|

THANKS A simultaneity for people. Utterances may be in any language or none. They may be: (1) sentences, (2) clauses, (3) phrases, (4) phrase fragments, (5) groups of unrelated words, (6) single words (among which may be names of letters), (7) polysyllabic word fragments, (8) syllables, (9) minimal speech sounds (i.e., phones, included or not within phonemes of any languages), or (10) any other sounds produced in the mouth, throat, or chest. Any utterance may be repreated any number of times or not at all. After a person makes an utterance and repeats it or not he should become silent and remain so for any duration. After the silence he may make any utterance, repeat it or not, again become silent, etc. People may continue to make utterances or not until no one wants to make an utterance or until a predetermined time limit is reached. All utterances are free in all respects. Non-vocal sounds may be produced and repeated or not in place of utterances. Anyone may submit any or all elements of this simultaneity to chance regulations by any method(s).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

1981 |

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Any vs. Every |

|

N'importe quoi |

|

References |

|