Quotes from:

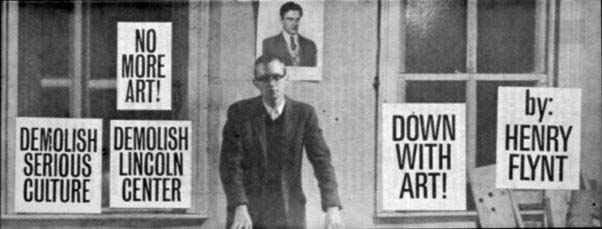

Henry Flynt © 1994

Concept art was meant to replace all of mathematics with an

endeavor which involved a Rorschach-blot semantics; and which

did not claim to be cognitive, at least not in the inherited sense.

Mathematics had already been disconnected from claims of realism;

and I was extending that disavowal to a disconnection from claims

of a priori truth. Concept art's value consisted in beauty, a

beauty which was non-sentimental. Later I would say that its value

consisted in "the invention of new mental abilities." Popularity

had nothing to do with whether this avenue was worth taking. With

that background, it was easy for people to object that concept

art had nothing to do with art. At the end of the original concept

art essay, I offered that thought myself. My observation was quoted

by the reviewer of An Anthology in the Times Literary Supplement

of August 6, 1964.[1] Admittedly, concept art does not belong

to a traditional artistic branch or medium (e.g. painting), and

it is not pictorially sentimental. On the other hand, there is

a very strong tradition in mathematics which claims artistic value

for mathematics (in effect). What is more, there was a period

in which "serious music" became intellectually pretentious and

nonsentimental--and the serious music establishment backed this

development.

Concept art was meant to replace all of mathematics with an

endeavor which involved a Rorschach-blot semantics; and which

did not claim to be cognitive, at least not in the inherited sense.

Mathematics had already been disconnected from claims of realism;

and I was extending that disavowal to a disconnection from claims

of a priori truth. Concept art's value consisted in beauty, a

beauty which was non-sentimental. Later I would say that its value

consisted in "the invention of new mental abilities." Popularity

had nothing to do with whether this avenue was worth taking.

Tristan Tzara's recipe for composing a dadaist poem, written

before 1920.

(In: The Dada Painters and Poets, ed. Robert Motherwell.)

To make a dadaist poem

Take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and

put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in

which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

Dutch mathematician L.E.J. Brouwer in "Consciousness, Philosophy,

and Mathematics": "... the fullest constructional beauty

is the introspective beauty of mathematics, where instead of elements

of playful causal acting, the basic intuition of mathematics is

left to free unfolding. This unfolding is not bound to the exterior

world, and thereby to finiteness and responsibility; consequently

its introspective harmonies can attain any degree of richness

and clearness."

I saw an analogy between the syntax which metamathematics arrived

at, and the computational character, or derivational process character,

of much new music. It was also evident that Young's word pieces

concerned the metasyntax of music. [Not using the rules that define

music, but twisting the rules.] The original concept art was a

genre which used visual displays or process objects or text. It

was a genre of syntax, or of derivational process. The notion

that the sort of structure which subtended mathematics could have

aesthetic value was already established from ancient times for

mathematics; and it had been proclaimed for new music.

Concept art was meant to exhibit syntactical structures which

broke the framework of objectification. We find that for the first

time ever, I used a perceptual illusion as a logical notation.

I relativized the existence of a derivation to the perceptual

agility of the "knowing subject" or "viewer."

Mathematics had to have been projected onto its logical tree-structure

so that this tree-structure could then be manipulated in a blind

and cruel way –– à la Tzara and Cage. I have

cited Tzara's recipe for making a Dadaist poem. One may pass directly

from that to my exposition of "Haphazard System" in Blueprint

for a Higher Civilization, pp. 97-99.

My positioning of the concept-art venture in the Sixties took

some peculiar turns. As I said, as of 1961, I had no hesitation

about committing to art. Mathematical cognition had been replaced

by the search for uncanny structure, for ideas such that the possibility

of thinking them at all was amazing. The defensible value of the

enterprise, I thought, was aesthetic. Thus it was that all of

mathematics and all of art (mainly music) which had syntactical

pretensions were to be collapsed to a new genre of art. It was

right to call it art, not "science." Even so, at the end of the

concept art essay, I noted that concept art was entirely unsentimental,

and I forthrightly acknowledged that that cast doubt on the appropriateness

of classifying it as art. (. . .) Then, around 1966, there began

a long period in which I revisited concept art; and reworked it

discursively. (As investigations in formal language and in models

of inconsistent theories –– to put it in the jargon

which my work seeks to supplant.)